Perhaps one of the most remarkable underdog stories in America belongs to Isaac Wright Jr., the wrongfully incarcerated Attorney who’s currently running for Mayor of New York. Wright’s story is a David and goliath tale of a man who refused to accept the fate that was imposed on him by a broken judicial system, and backed down every major player in government who contributed to his incarceration. In under five years, Wright went from having no legal background to spearheading an effort that would change New Jersey law at the state supreme court level. He used his intellectual prowess to creatively maneuver a legal strategy that involved testing his legal theories on inmates who were fighting charges similar to his, then using those changes as legal precedent to overturn the outcome of his own case.

To understand the legal mechanics working under the hood of Wright’s case, it’s instructive to recap the political culture of the 1990’s and the draconian policies put forth that set the stage for mass incarceration and the “annihilation” of black communities. “This was during a time when they were annihilating minorities in the system and in the community, and nobody cared.” Wright told Striped, “The thing at that time was ‘lock them up forever’ that was the cultural environment, the political environment and the criminal justice system. Lock them up and throw away the key.”

The war on drugs: Racist origins?

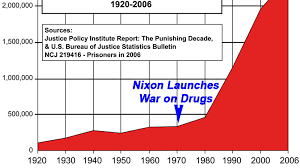

Wright was referring to the infamous “war on drugs”, a national political movement promulgated by the Nixon administration and marked by Nixon’s 1971 declaration of drug abuse being “public enemy number one.” After his announcement, Nixon increased federal funding for drug-control agencies and proposed strict measures, such as mandatory prison sentencing for drug crimes. The war on drugs was inspired by an uptick in drug use from prior decades, but many have speculated that the campaign had racist undertones. During a 1994 interview, President Nixon’s domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, provided inside information suggesting that the War on Drugs campaign had ulterior motives, which mainly involved helping Nixon keep his job. In the interview, conducted by journalist Dan Baum and published in Harper magazine, Ehrlichman explained that the Nixon campaign had two enemies: “the antiwar left and black people.” His comments led many to question Nixon’s intentions in advocating for drug reform and whether racism played a role.

It wasn’t until the mid-80’s under Ronald Reagan’s regime that incarceration rates really started to skyrocket. Reagan’s key legislation that would play a major role in shaping the future of mass incarceration was called The Comprehensive Crime Control act of 1984. It contained provisions that increased penalties for the possession of marijuana, abolished parole for criminals entering the system after 1987, and imposed rigid standard sentencing laws. This was at a time when America’s cultural zeitgeist was defined by anti-drug sentiments and national panic over crack cocaine’s debut on the streets. Alongside Raegan’s legislation was his wife Nancy Raegan’s “just say no” campaign intended to highlight the dangers of drug use.

Taken together, the new laws coupled with cultural outrage generated a national scramble for states to implement new laws and policies to combat drug crimes. New Jersey, was one of those states.

In 1986, the same year the Anti-drug abuse act was signed following the high profile death of the young basketball celebrity Len Bias, New Jersey put forth a law that would leave a legacy of racism, and destruction.

The Law was N.J. Stat. § 2C:35-3, AKA the “Drug Kingpin Statute.” It prescribed a mandatory life sentence, with parole consideration after 25 years, to anyone who financed, or managed one or more people in distributing schedule 1 or 2 drugs including marijuana, cocaine, LSD, and methamphetamine.

Wright was convicted in 1991 of purchasing two pounds of cocaine, and a jury found him guilty of violating the New Jersey Kingpin statue, which triggered a lifetime sentence. “I was literally facing an impossibility.” Wright told Striped, “I was a guy who stood up to the system. I was facing life in prison, I had a prosecutor who was one of the most popular officers in the state, friends with the governor and slated to be the next attorney general.”

In his previous life, Wright was a successful music producer and manager, managing big names at the time including Too much, Poor righteous teachers, Ragamuffin, and 3D. He was also involved with the Cover Girls, a group that his ex-wife was in, Sunshine Wright. Prison took his career away from him. “I was still rising, even though we were doing really well, in terms of where I was going, the sky was the limit. Guys like Puffy, Jay-Z, Biggie, some of the major players today, the only person doing anything at the time when I was on the rise was Russell simmons.” Wright said.

His work ethic and knack for success followed him into prison. Wright began plotting his route of escape as soon as he was issued a cell. “There was never a moment I thought about accepting anything.” Wright told Striped “I was gunna fall on the sword, I was gunna die fighting, if it took the rest of my life. I’d rather die in prison then accept something I didn’t do. This is something they didn’t understand about my personality, the more they fight the more I doubled down. It was wrong, it was unacceptable, it was my soul. Then I was seeing the things they were doing to everyone else. I didn’t understand it and the more I saw it the more I was convinced that this was something I wouldn’t allow them to do to me.”

The kingpin statute that Wright was convicted under made it easy to convict people. Keep in mind that the cultural backdrop of racism, and emerging attitudes of “lock them up and throw away the key” played a big part in wrongfully convicting innocent people. Wright wasn’t the only one. “It was very easy for them to convict me.” Wright told Striped “What people don’t realize about the law at that time at that time it was a time of mass incarceration and a war on drugs. All they had to do was to get people to say yes “Isaac was my boss.” What I did was, I compared the theory behind a drug kingpin is that it deserved a life sentence.”

Wright studied legal treatises and began working for a prison rights group called the Legal Inmate Association as a paralegal after they offered to house him in better conditions in exchange for his services. “A paralegal from the organization gave me a proposition. If I worked for them they’d get me out of the roach infested, rat infested basement area of the prison where I was staying. It was a no brainer for me” Wright told Striped. His success in law took off fast. “Within one year I was the top paralegals in the prison. Within 2 years I was one of the most powerful inmates in the entire prison system in New Jersey. My jail cell was an office. When I got arrested, all jails were overcrowded with the war on drugs. Always two in a one man cell, people slept under the beds. I had a typewriter, I had access to phones on the wall, for 8 hours a day, I had stacks of paper, a little desk, a filing cabinet. I operated like a lawyer would do with an office. I had a section in the jail where I spoke with visitors.”

Wright functioned like a real lawyer behind cell walls taking cases from other inmates and helping them with legal issues. But the whole time he was also planning an escape. With his newfound understanding of the law, Wright realized that in order to overturn his conviction he’d have to find a problem with either his conviction, or the existing law. He decided to attack existing law, and expertly calculated a plan to redefine the kingpin statute in the New Jersey supreme court, then use that interpretation as precedent to overturn his case. When a state supreme court rules on a law or defines the contours of a statute, the decision comes from the top down and affects anyone who was convicted on the statute. By redefining the statute in a way that was favorable to his case, Wright could effectively use the outcome to overturn his own case. All he needed was a “test” case to present to the New Jersey supreme court to see if his idea would work. Spoiler alert: it did.

His test subject was Ryan Alexander. Alexander was another inmate who was serving time under the kingpin statute that Wright met in prison. Alexander was convicted of delegating a crack cocaine operation to his underling Anthony Harewood, who would sell crack for $10/bag then distribute 70% of his sales to Alexander. Under the kingpin statute, the operation involved a schedule 1 drug, and the collaboration between two dealers. It resulted in a life sentence for Alexander.

Wright had a theory to get Alexander out. His reasoning started with the observation that the only other mandatory life sentence in New Jersey was for first degree murder. “Where you have reserved a mandatory life sentence only for 1st degree murder, then you have to make sure that a jury understands that this person is actually the leader of a narcotics trafficking network and the only way to do that is to be able to define to that jury the organization, the extent of it and the hierarchy of the person it cannot just be an agreement because if it is then you’ll have everyone on the street labeled as a kingpin.” Said Wright, “They ultimately agreed with me and that went to the supreme court in Alexander.”

Alexander’s case was a big win for anybody convicted under the kingpin statute. Before Alexander, juries were instructed by the simple reading or a summary of the statute. In Wright’s case, the judge paraphrased the statute “A person is a leader of a narcotics trafficking network if he conspires with two or more other persons in a scheme or course of conduct to unlawfully distribute schedule 1 drugs” According to this reading, almost anybody who has a role in a drug dealing operation can get a life sentence. Alexander’s case changed that by making it mandatory to instruct juries that a person can’t be a kingpin just because they dealt drugs, or delegated functions, but there needs to be an indication that they were at a very high level in the operation, that they were in the “upper echelons” of the scheme. Once Alexander’s case spelled this out, Wright used the ruling to bring his case to the supreme court of New Jersey where it was overturned.

The ruling in Alexander’s case helped potentially thousands of wrongfully convicted people get out of prison. Wright says the number that he directly influenced is about twenty. “Twenty is a number that’s been reasonably floating around but some of the new law I’ve made is still being applied to this day. By now it could be hundreds, even thousands.” Said Wright, “One of the laws I created early on was a challenge to the king pin statute at about 4 year in. I was convicted on the kingpin statute and several other counts where I had about 70 years. I had the life sentence on the kingpin statute and 70+ years on the others. I had created the challenge early on but I understood the politics in the judicial system. I decided to wait and put that theory in another prisoners case. Four years later, I asked him if I could help him, I put the argument in his case, I won, I created new law then used it to overturn my conviction. That law reversed every kingpin conviction in NJ.”

After he was released from prison, Wright earned an undergraduate degree in human services, then earned his law degree. He went on to co-produce the HBO series ‘For Life’ which was largely inspired by his story. Season two is coming up soon. Wright also recently announced his plan to run for mayor of New York, and as mayor he promises to focus on equitable housing, and social justice issues.

Wright had some words of wisdom for inmates who are interested in researching their own cases: “Pick up a law book”

“There’s an issue of law v. facts, and a specific foundational aspect of jurisprudence that even the most skilled lawyers don’t understand. Most people that are in prison, especially those who have gone past the appeals process, following black letter law is no longer a viable option for them. They followed it through the arrest, through the appeals process, and it didn’t work. Looking at this through a tunnel, the black letter law hasn’t helped them. This means that any success they’re going to get, they’re going to have to literally create it. And this is the reason you have so many people with these long sentences who could’ve gotten released but stay in prison because they’re in a state where they have to create their exit.

We all know what fiction and non-fiction is. The law is the only science in American society where exactitude is not relevant in its foundation. 1+1 = 2, math is an exact science. If the numbers don’t add up you get the wrong answers. In law, the foundation is fiction. When a person is found guilty by a jury, that finding is not a fact but a fiction. Because they’re found guilty doesn’t necessarily mean they are guilty. A jury’s verdict is a fiction that is accepted as fact by the law. Take the legal fiction of “accomplice liability” as an example. That’s a legal fiction in the law.

While I say yes, I believe every person in prison should pick up a law book and contribute to their own cause, the choice of representing themselves is a whole other choice of litigation where caution is the best order of the day and in areas of complexity, they really need an attorney.

The best starting point are treatises. Legal treatises are separated encyclopedias. One of the things you want to do is hone in on your case. If a person has a drug case, pick up a legal treatise on drug investigations and prosecutions because you learn important things like the chain of custody, field testing of drugs. A person can get 20 years for drugs and it was baking soda, because they didn’t know their lawyer could have challenged the chain of custody. They need to read areas related to their charges, and once you do that you can branch out.

What you also want to look for is whether there’s judges in the area who have written treatises. The best thing to do is quote law in treatises that the judges have written.

Prison is totally tragic, it’s indescribable the tragedy. The conditions are horrible, but the environment is a separate thing you have to navigate through. The human mind isn’t built to deal with prison. That’s why when people go in they come out an entirely different person. The human mind isn’t designed to deal with the monotony of imprisonment and trying to keep your sanity.

I had no idea the extent of my intellect until my intellect was severely challenged in ways I could never imagine and once that happened, I found myself, I found out who I really was.”

I , too, have a story to tell. Who do I contact to be published?

LikeLike

please email me at dresslerjake@gmail.com

LikeLike