Imagine a government-run correctional system that housed its prisoners in a facility filled with a colorless, odorless and noxious gas that causes various life-threatening illnesses such as lung cancer. Imagine that after incarceration, inmates are given no notice that they are inhaling this noxious gas, until it is too late and cancer has set in. Imagine that the government knew the prison was a deathtrap when it was built.

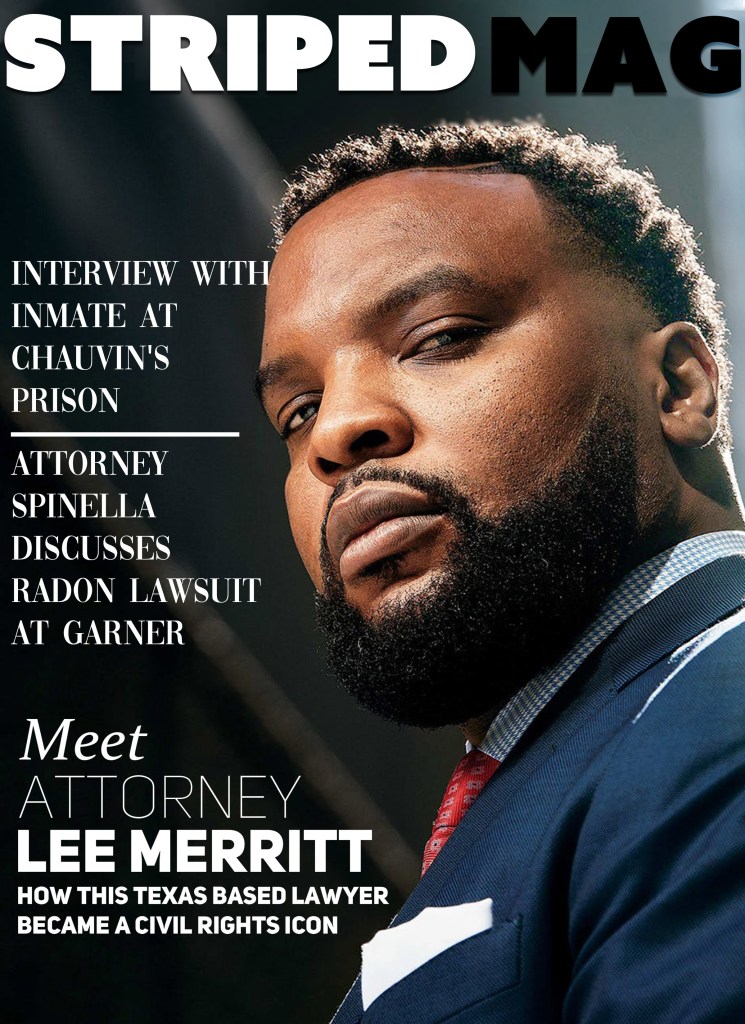

Unfortunately, this is not the stuff of a dark fantasy. It is a tragic reality right here in Connecticut. In 1992, the State of Connecticut opened the Garner Correctional facility in Newtown, in a location with radon levels that for exceeded acceptable levels set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). And the State knew it. While the inmates consisting of pre-trial detainees and post-conviction prisoners continuously breathed toxic levels of radon gas, the Department of Corrections (DOC) did no testing or exposure mitigation. Indeed, the DOC did not even tell the inmates what danger was in the air.

Radon is a radioactive gas created by the natural decay of uranium found in soil and rocks. Its found everywhere. It seeps up through the ground and lingers in the environment. To humans, it is odorless, colorless, and otherwise imperceptible. It is also the leading environmental cause of cancer in the United States, and the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), densely ionizing alpha particles emitted by short-lived decay products of radon (218p. and 214p.), can interact with biological tissue in the lungs, thereby increasing the chance of mutated cell colonies, DNA damage, and cancer.

There is scientific consensus that radon is deadly. Congress listed it as a toxic substance in 1988. The WHO and the EPA recommend that homes be tested for it prior to being inhabited. The EPA recommends homeowners mitigate radon exposure for air quantities greater than 4.0pCi/L, a measurement of radon exposure in the air. The WHO’s lower level of 2.7pCi/L is equivalent to smoking eight cigarettes per day.

The EPA and the U.S. Geological Survey designated the prison site in Newtown as a “Zone 1” area, having the highest average short-term radon measurement in a geographical area. The DOC knew this and nonetheless went ahead with construction. More distressing, the State built Garner on top of a former waste site. This made the prison foundation extra vulnerable to cracks, thereby, allowing see page of radon gas from the ground into the prisons air. All of this was made worse by an undersized heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system, and the similarly inadequate replacement which failed to refresh and circulate the air so as to adequately mitigate killer radon gas.

In 1996, a Department of Public Health survey, which tested well water in Newtown, revealed high levels of radon. This was well publicized. In 2001, another test revealed that a Newtown school which shared a well with Garner had uranium levels approximately eight times greater than the permissible levels set by the EPA for drinking water.

Despite this, Garner was not tested for radon gas until 2013 and early 2014 when an inmate teacher at Garner requested that the facility classroom areas be tested pursuant to Connecticut Statutes, which require radon testing in public schools. DOC officials only tested the school area and intentionally omitted testing the cell-block area. Of the areas tested, the results ranged from 5.0pCi/L to 23.7pCi/L.

Exposure to indoor radon at 10.0pCi/L is equivalent to smoking more than one pack of cigarettes a day; and exposure to indoor radon at 20.0pCi/L is equivalent to smoking more than 2.5 packs of cigarettes a day.

After the report was published, in May 2014, the DOC informed the employees that they could file a claim to preserve their workers’ compensation benefits should they develop medical conditions resulting from prolonged radon exposure at Garner. They did not warn prisoners. Apparently, the DOC deliberately chose not to test inmate cell blocks, since under state law to do so would have required the inmates to be advised in writing of the results.

My involvement in this case began with a Freedom of Information claim and subsequent hearing before the FOI commisions office pursued this calim at the request of Attorney Martin Minnella’, a Middlebury criminal defense attorney who represented several Garner inmates, three of whom had developed lung cancer. After considerable resistance by the State to comply with the FOI request, we eventually learned that on October 10, 2014, the DOC installed an emergency radon mitigation system to address dangerously elevated radon levels. Notably, the mitigation system was only designed to remedy the tested areas, and was intentionally designed to avoid mitigating excessive radon in the cell blocks. Again, the DOC failed to tell inmates about the excessive radon and absence of cell block mitigation.

On February 17, 2017, suit was filed in the federal district court, naming Michael Cruz and 10 other Garner inmates as plaintiffs. The named defendants were Department of Corrections Commissioner Scott Semple, the Garner Correctional warden, and the Directors of Correction, Engineering and Facilities Management. On January 26, 2017, the case was consolidated with a similar lawsuit brought by inmate Harry Vega, resulting in the presently pending case of Harry Vega et al. v. Scott Semple, et al.

The claim in Vega arises under the Eight Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments.” The United States Supreme Court originally applied this clause solely to the prevention of torturous or barbaric punishment of criminal defendants before or after conviction. As stated in one early Supreme Court decision, “cruel and unusual punishments” has applied to such punishments as being burned alive, drawn and quartered, dismembered, and public dissection.

The late 1960s and 1970s brought a series of federal lawsuits filed by prisoners claiming Eighth Amendment violations due to an appalling absence of healthcare in prisons across the country. These cases included allegations of untrained prisoners diagnosing, treating and prescribing medications; correctional officers preventing prisoners from attending sick calls; outright denial of medical care; and zero mental health care. In 1967, the Governor of Arkansas, Winthrop Rockefeller, released a report documenting horrific medical care conditions at the Arkansas Tucker Prison Farm. A prisoner with no medical training “ran” the medical program where he dealt illegal drugs, sold medical leaves of absence, and tortured patients with electric generators. Soon after, similarly sickening “medical programs” in Alabama, Texas, Pennsylvania, and New York were also revealed.

At first, the Supreme Court conceded that although such the conditions were unsatisfactory, they did not qualify as cruel and unusual punishment. But things changed in 1976, with Estelle v. Gamble. In that case, the Court held that prisoners have the right to adequate medical care, and that evidence of “deliberate indifference” to a prisoner’s serious medical needs constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Now cases around the country followed the ruling in Estelle, holding that adequate healthcare means “services at a level commensurate with modern medical science and prudent professional standards.”

In 1993, the Supreme court decided the game-changing case of Helling v. McKinney, in which it held that the threat of substantial future medical harm constituted a valid Eight Amendment claim. William McKinney, a prisoner in the Nevada State Prison, shared a cell with an inmate who smoked five packs of cigarettes a day. McKinney alleged that he suffered from nosebleeds, headaches, chest pains, and lack of energy due to second hand exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS). Following dismissal of the case by the trial court, McKinney appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

The Court held that the Eight Amendment protects against serious risk of harm as well as present medical harm. In upholding McKinney’s claim, the majority pointed to precedent holding that the Constitution mandates safe prison conditions. In McKinney’s case, prison officials violated the Eighth Amended by acting with “deliberate indifference” to “levels of ETS that posed an unreasonable risk of serious damage to his future health.”

Back to the Garner case. Shortly after the case was filed, the defendants asked the court to dismiss the complaint on the grounds of “qualified immunity.” This defense is available in cases where there is no clearly established law at the time which would have given prison officials notice that they violated the law through their actions or inaction. However, in this case argued that qualified immunity was not available since there was clearly established law at the time after the Helling decision. Judge Janet Bond Arterton, the New Haven federal district judge hearing the case, denied the Motion to Dismiss for all conduct occurring after the Supreme Court’s decision in Helling, which was issued on June 18, 1993. In the Court’s view, the Helling decision provided fair warning that the failure to mitigate dangerous levels of radon in the prisoner cell blocks constituted deliberate indifference by prison authorities to known, serious medical needs

The DOC immediately appealed Judge Arterton’s decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City. The principalquestion on appeal was whether qualified immunity protected the DOC from suit. In the Second Curcuit’s view, the Helling decision was again key. The Court noted that in 1993, the danger of ETS was a recognized health menace, and no prison official could deliberately ignore it without violating the Eighth Amendment. If this was so for ETS, it is particularly true for radon; as the Court wrote: “[i]f anything, knowing or reckless exposure of prisoners to radon, given the facts alleged by Plaintiffs, is more obviously unconstitutional than exposure of prisoners to ETS was in 1993.”

Moreover, in 1993, the danger of ETS was still being debated; radon, on the other hand, was not. That same year, the International Agency for Research on Cancer and Congress added radon to the Toxic Substances Control Act. In the Court’s view: “if a reasonable prison official was aware of the future risk of ETS by that point, then surely a reasonable officer would have been aware of the future risk of a known carcinogen like radon.”

The Second Circuit concluded that from Garner’s inception, state officials had knowledge of an unreasonable risk of serious harm posed by excessive radon exposure but did nothing to abate the risk. Furthermore, the DOC deliberately chose to build the prison on a former waste site previously identified by a U.S. Geological Survey as a location with dangerously high radon levels. These facts and the Department’s subsequent inaction demonstrated deliberate intent, as evidenced by the failure to respond to various triggering events, such as the discovery of unsafe uranium levels in the school that shared Garner’s water supply and, most significantly, the discovery of unsafe radon levels in Garner’s classroom areas.

The Second Circuit also found that there was a “failure to take any steps to abate the risk of excessive radon exposure which violated the Plaintiffs clearly established right to be free from deliberate indifference to exposure to excessive radon gas, a toxic substance that imposes a serious health risk – a right clearly established in Helling.”

The Second Circuit rejected the Defendants additional request to dismiss based on the doctrine of sovereign Immunity. This doctrine arises from the Eleventh Amendment’s prohibition of lawsuits against a state brought by citizens of that state or another. There is an exception to this rule: in cases where an individual seeks to end future conduct by a public official to end an ongoing violation of federal law, suit may be brought.

In Garner, the exception applied since the inmates sought relief from an ongoing constitutional violation: the deliberate indifferenceto serious medical needs of incarcerated persons facing future medical harm. Therefore, the Plaintiffs were entitled to basic radon-related medical attention, such as baseline x-rays, and prospective medical monitoring including physical exams, chest x-rays and pulmonary CAT scans. Follow-up health care treatment for all diagnosed medical conditions as identified by the National Academy of Sciences; the National Cancer Institute; the American Medical Association; the EPA; and the WHO were also required.

Shortly before oral argument on the Motion to Dismiss, the DOC enacted a new administrative directive that required radon testing and mitigation in corrections facilities throughout Connecticut. Based on this directive, the Defendants argued the case should be dismissed since there was no longer an ongoing violation. The Court disagreed, stating: “[given the] long history of alleged cover-up and failure to remediate radon” the harm to inmates was clear and must be addressed by court action.

The Second Curcuit Court concluded its decision by remanding the case for further discovery on the issue of the Defendant’s knowledge of the radon risk alleged, and arguments on the size and composition of the class proposed by the plaintiff’s motion for a class action

Once a citizen is convicted and imprisoned, the state controls all the things they need to survive: food, water, even the very air they breathe. This is also true for medical care since a prisoner cannot call a doctor or drive to a hospital. To someone locked in a cage, the availability of decent medical care is a matter of life and death.

Prison wardens and prison guards are now clearly on notice that the Eighth Amendment not only applies to barbaric punishments, but to the threat of serious medical harm; a jailor cannot turn his back to a prisoner who is dying before his eyes from a preventable disease. To deliberately deny necessary medical services is tantamount to enhancing punishment beyond the sentence imposed, rendering it “cruel and unusual.”

The need for reasonable medical care is particularly important as COVID-19 rages through our over-crowded prisons. The inmates of the Garner Correctional facility live under an additional ominous cloud of medical danger: that of the ticking time bomb of radon poisoning the air of every cell block.

It has been said that as a society, our appetite for imposing incarceration is as voracious as our aversion to protecting prisoners once the prison door clangs shut. Litigation and the courts are the last real remedy to ensure prisoner health and safety. For the Garner inmates exposed daily to radon gas, the fate of their health and well-being now rests with the courts